The Weight of Judgement: The History of Capital Punishment in Ontario County, NY

To listen to this blogpost, click here! You will find additional photos and visuals.

If I asked you to name which states in the U.S. have the highest number of executions, which states come to mind? Are the first ones you think of Texas and Oklahoma, two states that have been the most active in executing death row inmates since the Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty in 1976? Or is it Florida? Known for high profile executions of serial killers Ted Bundy and Elaine Wuornos.

Did you ever consider New York? Between 1608 and 1976, New York State executed 1,130 individuals, only second behind Virginia during the same time frame who executed 1,277 people. New York State hasn’t actually executed anyone since August 15th, 1963. Eddie Lee Mays, sentenced to death in 1962 for the murder of Maria Marini during a robbery in East Harlem concluded NYS’s era of capital punishment with his execution in Sing Sing prison’s electrical chair, referred to as “Old Sparkey.”

Even with no executions since 1963, New York still stands as the state with the third most executions in the country. But New York’s place in the history-books of capital punishment isn’t limited to just a large number of executions. In the interest of humanity, former New York governor David Hill established a Commission to Investigate and Report the Most Humane and Practical Method of Carrying into Effect the Sentence of Death in Capital Cases – the Gerry Commission, also known as the Death Commission in 1886. The commission consisted of only three members, one of whom was Buffalo dentist Alfred Southwick, a prominent euthanization by electrocution advocate who had been experimenting with electricity on animals since 1881. The Death Commission ultimately recommended New York State adopt electrocution as the formal method of execution in the late 1880s.

The commission also recommended that the state establish execution chambers at Auburn State Prison, Sing Sing, and Dannemora. Before the commission’s recommendations, it was common practice for counties in the state to handle their own executions. Cases, and the accused were tried in the county where the crime occurred, and if ultimately sentenced to death, were executed in the same county. By 1888, New York State passed a bill establishing electrocution as the official method of execution in the state, and on August 6th, 1890, a man named William Kemmler was led down to the basement of Auburn State Prison’s administration building and placed in the country’s first electric chair. Although the establishment of the electric chair was seen as a more humane progression away from hanging, the electrical execution of Kemmler resulted in a gruesome scene which some eyewitnesses described as lasting four minutes long. Other witnesses to the execution who had been proponents of electrocution dismissed those claims, and argued that Kemmler had died instantaneously and painlessly.

Only two years earlier, and just 40 miles west of Auburn State Prison, Ontario County hanged their second, and unbeknownst to them then, final prisoner in a scene also described as gruesome. John Kelly’s hanging in Canandaigua on July 10, 1889 became local folklore, with murmurs and claims that the brutality in his hanging resulted in the creation of the electric chair in nearby Auburn. While the historical timeline disputes this rumor, both of Ontario County’s executions began and ended in a dramatic fashion… easy fodder for any urban legend creation. However, more than 130 years later, both executions, which at one point gripped residents of the county and dominated news cycles, have now seemed to slip from our cultural consciousness and have been forgotten with time.

The utilization of capital punishment in Ontario County in the late 1800s brought with it proponents and opponents of the issue, and much like today, was divisive not only across New York State, but also throughout the county.

Let’s discuss the Eighmey-Crandall murder. A high-profile crime, trial, and subsequent execution which served as Ontario County’s first death penalty case.

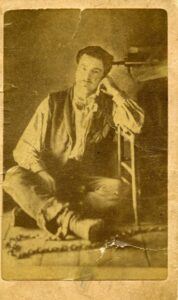

Charles Eighmey was 23 years old when he began working on the farm of George Crandall near Oaks Corner in Phelps. Within a year of his initial employment at the Crandall farm, Charles was arrested for the murder of George Crandall – accused of striking Crandall with a potato hoe over 11 times and eventually killing him.

Born July 16, 1850 in Phelps to parents Wylie and Elizabeth Eighmey, Charles had three older brothers, one older sister, and two younger sisters. His family’s farm was just a few miles south of the Crandall’s property in Oaks Corner.

In 1871, a 21 year old Charles began living and working at Franklin Webster’s farm, also in Phelps. By fall, Charles had traveled to Lapeer, MI, just outside of Flint, where his brother William owned a farm. After a short time, Charles moved to Lansing, where he was hired as an animal handler for the J.E. Warner & Co.’s Great Pacific Consolidation Menagerie and Circus. He was primarily responsible for the “cat animals” as he later described to a reporter with the Democrat & Chronicle.

“April 13th, 1872,” describes Charles, “we showed in Lansing, and then traveled through Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, Kentucky, and other states until fall when we returned to quarters at North Lansing. My folks wanted me to come home and I did.” It was this decision to return home that ultimately began Charles’s journey to the gallows.

Through the spring of 1873, Charles worked on his family’s 31 acre farm, with help from his brother who had returned from Michigan. It was around this time that George Crandall, who lived only a short distance from the Eighmey farm, asked Charles to assist him in caring for his own farm. Charles agreed, and on April 1st, 1874, after having planted a garden on Crandall’s property, began living at the Crandall farm with George and his wife Charlotte Humphrey, known around the community as Dott.

George and Dott were both in their mid to late thirties, and had just moved to their farm in 1871 – the same year Charles was working at the nearby Webster farm. Charles claimed that in the year after he returned from Michigan, and before he began living full time on the Crandall farm, he had lent George a large sum of money, as well as several business transactions that also included corn and a mule. Charles stated George would repay various amounts of the money intermittently, but a large portion was never paid back. Charles would make some return on the garden he had planted on the Crandall farm, selling the produce down in Geneva and in Phelps. Charles claimed his relationship with George was without any serious quarrels until neighbor Franklin Webster began regularly visiting the Crandall farm.

The first serious dispute between Charles and George transpired over the building of a shed during dinner. The following account comes exclusively from Charles, and should therefore be judged accordingly. Charles claimed that when he asked George what kind of shed he planned to build and how he was going to build it, George angrily shot back and said, “Why, you fool, I am going to build a shed; not of iron or stone, but a shed with a board roof, and I don’t want any of your bossing about it, either.”

As tensions rose, Charles left the dispute to tend to his garden. When he returned from his garden, George had gone to Geneva in search of wood. Dott, George’s wife, told Charles that George expected Charles to dig post holes for the shed while he was in Geneva. Confused, Charles explained that George had not given him any direction on how he wanted the posts to be dug. Upon George’s return, another quarrel between Charles and George began, with Charles ultimately deciding to leave George’s property. As he headed to his room in the Crandall house to retrieve his property – Dott pleaded with Charles to not leave. George followed Charles into the house, and when Charles had returned from his room with belongings in hand, he asked George to settle all debts so he could leave. Again, George and Charles began to quarrel, with George threatening to beat Charles’s brains out of his head. Dott intervened between the two men, pleading with George to calm down. Though with good intentions, she soon found herself shoved out of the room by her husband. Charles, done arguing with George, left the property for his family’s farm, and didn’t return to the Crandall property until the next day.

Thinking a night would cool any remaining tension between the two men, Charles returned to the Crandall farm the next morning to find a still aggravated George. After arguing further about the shed, George told his wife that if she attempted to intervene between him and Charles ever again, he would kick hell out of her. George again decided to leave for Geneva to find more wood for his shed. With George gone, Dott confided in Charles that her marriage was filled with George’s constant arguing, and accusations. Charles again reiterated his intentions of leaving the Crandall property permanently, but Dott begged for him to stay, reminding Charles of his garden on the property, and pleading with him to stay to protect her from George. Ultimately, Dott’s begging worked, and Charles remained on the Crandall property.

Only a short time after deciding to stay on the property, Charles again attempted to leave, hoping to join the Robinson Circus that had stopped in Geneva after another argument with George. Dott again asked Charles to stay, and told the young man that she preferred his company to that of her own husband, and that she in fact loved Charles more than George. Neighbor Franklin Webster began discussing with Charles how he had a legal right to kill George if another confrontation began between the two. Charles explained he had no intention of laying hands on George. Franklin told Charles that George was a loud and pompous man, and killing him would be a favor to Dott, who was a good woman. If George was out of the picture, Charles and Dott could have a good life together, and Charles could live like a king, explained Franklin.

George Crandall’s murder occurred July 2nd, 1874, while hoeing potatoes in his field. The only two witnesses to the crime were Charles and George. Charles claimed the murder was orchestrated by Dott, who informed him how best to use the hoe to kill George. She would wave a handkerchief from the house to Charles in the field to inform him that he and George were no longer visible from the road, and even gave him a shot of whiskey (only the second or third drink Charles had ever had in his life) before he joined George in the potato field. George was a few rows ahead of Charles, hunched over when the first strike of the hoe hit his skull. As he fell, Charles struck him again. Later, the autopsy completed at the Geneva Medical College revealed 11 strikes in all, two that were fatal, and two to three that had the potential to be fatal blows. Charles claimed that he struck George only twice, and had no memory of the 11 blows.

As George lay in the field dying, Charles snapped George’s hoe and cut his own hand to make the crime appear in self defense. Charles summoned Dott from the house to come see George in the field, and called for Franklin in the neighboring field. Both Charles’s father and brother appeared in the field. As Charles held George’s head in his lap, he began to weep. Charles opened his mouth to speak, but Franklin shouted at him to shut up. “Don’t say anything,” shouted Franklin, “and don’t make no explanations to anybody.” The four men carried George’s body back to his house, where a doctor and the police were called.

Once held in jail, it was Franklin Webster who told police that he had heard Charles on several occasions admit that he wanted to kill George. Just a day before the murder, Charles claimed that while in Crandall’s barn, Franklin had informed him that if Charles did kill George with a hoe, he would tell police that he saw the whole incident, and that George did in fact strike Charles first. Charles later told a journalist with the Democrat & Chronicle that he believed Franklin instigated the murder with intentions of always turning on Charles in hopes of buying Crandall’s property and expanding his own farm.

When Charles learned that both Dott and Franklin had made statements against him to the police, he dictated and wrote several confessions. At the time of his arrest, Charles was described as low intelligence. His written confessions, reprinted with their original spellings and wording in an 1876 pamphlet show Charles’s struggles with literacy, a fact specified in the pamphlet.

Just hours after George’s death, Dott was asked by police if she wanted to see Charles in jail. She agreed, and a long handshake and whispers between the two were described. Dott was later asked if she wanted to visit Charles in jail, however this time occurred after Dott herself was brought to the jail with a warrant due to Charles’s confessions that she had instigated her husband’s murder. From his cell, Charles reiterated to Dott his claims that she and Franklin encouraged him to attack George. She refuted his remarks, and said Charles was looking to detract blame from himself to others. After Dott’s interview with police, she was released, and never again detained for the death of her husband, though gossip around the county of her involvement never quite quelled.

Charles’s trial lasted five days, and was prosecuted by D.A. Edwin Hicks. The scandalous nature of the trial and resulting attention from the community caused initial reports to state the trial would be held in Syracuse to avoid a biased jury. Ultimately, the trial was held in Canandaigua. 12 jurors were selected for the case:

Harendeen, farmer, Canandaigua. Ward P. Mann, butcher, Canandaigua, David H. Osborn, farmer, Victor, William H. Allen, farmer, Bristol, Robert Coons, farmer, Naples, Daniel B. Bartholomew, farmer, Naples, George C. Mather, farmer, Canandaigua, Simeon Kingsley, merchant, Shortsville, Nathaniel Gifford, farmer, Canandaigua, Avery Ingabeth, farmer, South Bristol, Delos Doolittle, mechanic, Canandaigua, and Joseph Dibble, farmer, East Bloomfield.

On the stand during his trial, Charles again reiterated he had no prior intention of killing George Crandall. D.A. Hicks disputed this claim, and urged jurors to convict charles of first degree murder, which would result in a death sentence. Tthe jury returned their verdict after 18 hours of deliberation, and found Charles guilty of first degree murder. At his sentencing, the judge criticized Charles’s demeanor throughout the trial, stating Charles showed an inaccurate belief that he would not be found guilty of the crimes. The judge sentenced Charles to be hanged on July 2nd, 1875, the first anniversary of the crime. As the judge declared his sentence, Charles’s father Wylie broke down in court, screaming, “Oh my innocent boy! You will kill an innocent boy.” Charles’s defense attorney immediately appealed the ruling, and his execution was stayed. After two stays of executions to allow appeals to be seen by higher courts, ultimately ending with then Gov. Tilden denying an appeal to commute the sentence to life imprisonment, Charles Eighmey’s death was finally scheduled for September 8th, 1876. Ontario County began preparing for its first execution.

In the late 1870s, Ontario County was home to around 49,000, with around 5,000 of those individuals living in Canandaigua, the county seat. The Eighmey trail was a spectacle throughout the county, even before the death penalty was handed down. During the trial, a Democrat and Chronicle reporter described the court as “densely packed.” “Rarely, if ever before,” wrote the reporter, “have the good people of Ontario County been so thoroughly stirred up by any crime taking place within its limits as is the case with the Eighmey – Crandall homicide.” Spectators at the trail were described as bringing their dinners to court so they did not have to leave the trail to get food. A large number of women also attended the trial as spectators, noted as showing the wide appeal of the case.

The preparations in the county for Charles’s hanging generated only more excitement and discussion from residents. A brief sentence in a Democrat & Chronicle article the day after Charles’s execution describes the debate regarding capital punishment to have been a topic of conversation on “street corners, hotels, and saloons” in the then Village of Canandaigua. In a letter from Gov. Tilden’s personal secretary to Ontario County Sheriff Boswell, the governor’s secretary stresses the importance of Eighmey’s execution to be professional, writing:

“Sir: the governor directs me, in view of the approaching execution of Charles Eighmey, to call your especial attention to the provisions of the statute relating to the subject. It is the evident design that executions should be private, and that no one should be permitted to witness the same except such as are required to be present. His excellency expects this intention of the law will not be evaded by the appointment of unnecessary special deputies or otherwise. With respect to the details which the law leaves to your discretion, he hopes that you will take the greatest pains to discharge your duty with all decency, dignity, and humanity. – Charles Stebbins.”

By Charles Eighmey’s execution in 1876, public executions had been legislated out of New York State. In 1828, county sheriffs were given the discretion to conduct executions within the confines of prison yards with a small audience, but by 1835, the New York State legislature had mandated executions be private through a bill originally presented by Erie County representative Carlos Emmons in 1834. Despite the mandate, many county sheriffs continued to conduct public executions, due in large part to the influx of business local merchants, such as taverns and grocers, saw on hanging day.

The move away from public hangings in New York State in the mid-1800s could be viewed now as a direct result of changing attitudes towards capital punishment and increasing distate in the practice by citizens. However, it wasn’t the practice itself so much as the atmosphere surrounding the event that was seen as distasteful by an emerging middle-class that prided itself on sobriety and self-control. Public executions brought with it a carnival-like scene that saw the mixing of classes, sexes, and races, and often heavily featured drunkenness and rioting. The emerging middle-class pushed for the strict segregation of “masculine” and “feminine,” and believed that moving executions indoors would allow the practice to continue without abolishment, but protect women, children, and “the dangerous classes” from the moral corruption of hanging day. Once private executions began in earnest, women rarely if ever received an invitation to attend.

In preparation for Ontario County’s first execution, Sheriff Boswell enlisted the Rochester Militia to serve as security for the event. The scaffolding was built on the west-side of the jail-yard in Canandaigua, using the same build plan for the scaffold that was used in John Clark’s hanging in Rochester, who had walked onto the platform smoking a cigar. Similarly, the noose and rope were property of Monroe County, and had been used at the hangings of Ira Stout, John Clark, and Joseph Messner of Rochester, as well as Ruloff from Binghamton, and Thomas B. Quakenbush from Batavia. The rope was 18 feet long, with a noose half an inch thick made of shoe thread.

Adhering to Gov. Tilden’s request, Sheriff Boswell issued only a limited number of invitations to witness Charles’s hanging inside the jail-yard. However, by 9 A.M. the morning of the execution, a large crowd of residents had already formed around the jail, and did not leave until long after Charles’s body was removed from the jail. Even throughout the end of the day, it was reported that large crowds lingered on the village streets, hoping to hear accounts of the hanging from individuals who were issued an invitation. Much like the trial, Charles’s execution was one of theatrics and drama. While standing on the scaffolding, just minutes before his hanging, Charles asked Franklin Webster to come forward so Charles could once again reiterate that he was coerced by Franklin Webster and Dott Crandall to attack George Crandall. When Franklin Webster attempted to respond to Charles’s claims, he was quieted down by the crowd inside the jail yard. The D&C reported Charles’s hanging was the first in which no violent contractions from the body during the hanging were seen. The final reporting of the Eighmey case from the Democrat & Chronicle ended with this acknowledgment:

Sheriff Boswell and his deputies are entitled to great credit for the manner in which preparations for the event were made and the perfect order and decorum that prevailed during the execution. Nothing could be done better or more conscientiously.

After Charles’s death, his father Wylie was responsible for paying around $1875 incurred in his son’s defense. Franklin Webster left Oaks Corner, moving to Lyons, Brighton, and eventually dying in New York City in 1907. In 1881, he was accused of committing forgery and fraud, a crime he had committed and been arrested for in 1868.

Dott Crandall continued to live her life in Phelps, but was reportedly shunned by the town’s residents for the rest of her life. In 1885 she remarried, and ultimately died in 1889 of chronic hepatitis.

Charles was buried next to his family in Armstrong Cemetery in Phelps.

Ontario County had concluded its first execution, but another capital punishment trial was looming.

The execution of John Kelly in Canandaigua on July 10th, 1889 was not the success the Eighmey execution was believed to be. By Kelly’s execution in 1889, Ontario County police forces were no longer led by Boswell who had overseen Eighmey’s execution, but rather Sheriff Corwin, who had taken over for Sheriff Wheeler in January of 1889. On his execution day, John Kelly referred to Sheriff Wheeler as a “man who said much and did little,” while he believed Sheriff Corwin was a “man who said little, and did much.” While Charles Eighmey’s crime was seen as sensational and melodramatic, Kelly’s case was darker and seedier. Even his execution proved more gruesome and heinous than Eighmey’s quick death.

On November 6th, 1888, John Kelly killed Eleanor O’Shea after hitting her over the head with a hammer. Both Kelly and O’Shea worked for George Kippen, a wealthy farmer from Geneva. O’Shea worked for Kippen, who was a widow, for six years as a housekeeper before her death. Kelly, who by the time of the murder was in his late-40s, was a hired hand on Kippen’s farm. It was believed that Kippen’s estate was valued at more than $100,000, though he was described as a man of modest habits. Kippen’s only surviving child, daughter Margaret, still lived at home though she was already in her early 30s. Margaret was described as “demented,” in several articles relaying the details of the crime. From trial proceedings, it is more likely that Margaret suffered from developmental delays, and although had the appearance of a 30 year old woman, was more likely operating with the mental capacity of a child.

Ten years before the crime, John Kelly was living with his wife, his son Timothy, and two daughters Belle and Mary. Timothy described his father as becoming suddenly and violently an alcoholic around this point in time. Several public drunkenness arrests were made against Kelly, and eventually his wife kicked him out of their home. By the time Kelly was working on the Kippen farm, he was staying in a nearby boarding house, where his room was described as being of filth and squalor.

Late November 6th, Kelly returned to the Kippen farm after voting in elections in Geneva. Margaret Kippen, upon hearing Kelly’s return, was exiting the Kippen house to visit Kelly in the barn. Eleanor O’Shea chastised Margaret for her interest in having sexual relations with Kelly, and forbid her from seeing him. Undeterred, Margaret met Kelly in the barn. When Margaret returned, Eleanor again criticized her for seeing Kelly. Margaret explained that she would “make free with John if she wanted to.” By this time, Kelly had also entered the Kippen household, and was being chastised by O’Shea for his relations with Margaret. Kelly argued with O’Shea denying the accusations, and asked O’Shea, “Do you say that I’m a whoremaster?” “Yes, I do,” responded O’Shea. Upon hearing her response, Kelly immediately punched O’Shea, a woman in her late 40s, in the face. He had previously been arrested and fined $15 for assaulting her the previous year. As she lay on the floor, Kelly kicked her breasts and head with his boots. O’Shea then rose from the floor and grabbed a teapot from the stove, threatening to scald Kelly with the water. She swiped at Kelly with the teapot, and Margaret soon joined the fight, and was able to take the teapot away from O’Shea. Once disarmed, O’Shea grabbed Margaret, and pushed her down a hallway where she remained.

As fighting continued, Kelly grabbed a hammer from a mantle place. O’Shea stood on the opposite side of the room from Kelly, having been separated by another of Kippen’s hired hands, a 68 year old man named Thomas Mahar. According to Mahar, Kelly coolly walked over to O’Shea and asked her again, “Can you prove what you said? Do you say I am a whoremaster?” “I do,” responded O’Shea. Kelly took the hammer, and struck O’Shea on the top of her head. She fell to the ground, but crawled towards a chair. While O’Shea sat on the chair, Margaret returned to the fight, and taking a stick of firewood, began beating O’Shea several times. O’Shea eventually stumbled into the kitchen pantry, where she closed the door. She was heard falling to the floor, where she laid dying in a pool of her own blood. She was not checked on until the next morning, and eventually died later that night.

Only moments after the attack, Kelly had gone to George Kippen’s room and alerted him to a disagreement. However, no one checked on O’Shea. Kelly again reiterated that if anyone were to call him a whoremaster he would kill them. After his arrest, Kelly claimed that a man cannot be held responsible for his actions when “everyone is picking on him, and his anger gets the better of him.” It was later determined that at the time of the murder, Kelly was drunk.

Kelly’s case was prosecuted by D.A. Clement, and consisted of jurors: William S. Crippen, Bristol, William Salisbury, Phelps, Joseph J. Berry, Farmington, Samuel L. Tozer, South Bristol, D.A. Goodrich, Gorham, Oliver Swift, East Bloomfield, Miles H. Green, Canandaigua, Joseph T. Duck, Geneva, Everett Lord, West Bloomfield, James Ransom, Victor, Omer P. Case, Hopewell, and James J. Olmstead, Bristol. Kelly was represented by attorney Edwin Hicks, who prosecuted the Eighmey trial.

Before the jury was selected, each potential juror was interviewed and asked a set of questions by both D.A. Clement, and Kelly’s attorney Hicks. Notably, these questions included if the potential juror opposed capital punishment, and if they would have any conscientious scruples against finding a verdict of guilty in a case where the death penalty might be inflicted. The potential jurores who stated they were against the death penalty were 33 year old Dennis Seymour, a farmer from West Bloomfield, 38 year old Richard Gage, a farmer from Gorham, Edwin Knauss, a hardware store clerk from Manchester, Elmer Halliday, a farmer originally from Michigan living in Manchester, and Henry M. Beeman, a farmer from South Bristol. They were all excused from serving.

Similarly to the Eighmey trial, a large crowd of people waited outside of court to secure seats when Kelly’s trial began. On Dec. 20th, 1888, just a few short days after the start of Kelly’s trial on Dec. 18th, the jury found Kelly guilty of first degree murder. The Judge sentenced him to hang on January 24th, 1889. A motion for a new trial was denied, and his appeal was denied. Kelly’s new execution date was set for July 10th, 1889.

Ontario County Sheriff Corwin was assisted in the execution by Monroe County Sheriff Hodgson. It was estimated that over 700 people requested interviews with Kelly the day before his execution. He refused to see any visitors except his family and religious advisors. The day of his execution, Kelly’s children again visited him in jail. His son Timothy left the jail-yard before the execution, and walked towards the Canandaigua Hotel where he rested on the building’s steps. A small group of men were next to him on the stairs discussing the impending execution. Timothy reportedly defended his father, and said he was a good man who fell victim to drinking. He told the men that anyone is liable to have that happen, including them.

Unlike Eighmey’s execution, Kelly’s final words were not dramatic or sensational. Kelly reportedly rambled for several minutes incoherently before again claiming that any man would have killed Eleanor O’Shea due to her personality. His final words were, “I am going soon. Goodbye. You’re too slow.” He was shackled as he walked from the jail to the scaffold, and the actual shackles he wore that day are in the Ontario County Historical Society’s collection.

When the drop fell at 12:05, Kelly’s neck was broken instantly. Blood ran from his mouth and nose down his body, forming a pool on the floor. He was pronounced dead at 12:07. When the cap was removed from his head, there appeared a large razor-like gash around his neck from the noose… his face fixed on a distorted expression. The body hanged for 16 minutes due to the undertaker’s late arrival.

Following Kelly’s execution, George Kippen institutionalized his daughter, and she later died at Willard State Hospital in 1925.

Kelly’s execution did not elicit the same feelings of success as the Eighmey execution. And though local lore eventually associated Kelly’s disturbing execution with the end of hangings, the transition towards state operated electrocution had already begun even before Kelly’s trial in 1888. Though Ontario County was no longer responsible for any future executions, the death penalty was still a prominent issue amongst Ontario residents.

In 1893, Rev. J.T. Crumrine wrote a letter to the Democrat & Chronicle editor, addressing his support for the death penalty, and arguing why religious leaders should be in support of capital punishment. Rev. Crumrine was a Presbyterian pastor from Shortsville. Clergy support for the death penalty in the late 1800s was common amongst certain religious sects. Unitarian churches, however, during this time were the strongest critics against the death penalty. Other religious leaders found executions, especially public executions, an important opportunity to increase their authority and prestige in an era where both were dwindling for American clergy. Executions allowed religious leaders a platform and captive audience for their sermons, and also showed the power of God, as well as their own power, to save the souls of the prisoners facing execution.

In 1899, first-year Assemblyman for Ontario County Jean L. Burnett introduced a bill to abolish the death penalty in New York State. Burnett graduated from Canandaigua Academy in 1889, the same year John Kelly was executed. He earned a law degree from the University of Michigan, and returned home to Canandaigua to practice law. Burnett’s bill allowed juries to apply mercy on first-degree murder cases, which would then make punishment the same as second-degree murder, which was life imprisonment. The intention of the bill was to halt executions, and eventually assist in the formal repeal of the death penalty. In an interview with the Demcorat & Chronicle, Burnett admitted that his intention was to end the death penalty, but he did not believe a bill doing so would be favorable enough to pass. He explained that he had always been an opponent to capital punishment, and believed it was a relic of barbariasm, which belonged in the era of the Inquisition, and not in modern enlightened society. Here are Burnett’s own words on the subject:

“Ten years hence the people of this state will look back with wonder to realize that they clung so long to a practice which represents nothing, and embodies nothing, but the primitive impulse for vengeance and revenge – the very instinct which the death penalty itself is designed to suppress. Its absolute failure as a preventative of homicide is acknowledged by every statistician, for the experience of society has demonstrated that murder by the state will not prevent murder by the individual. There is in reality no argument left for it except the old ‘lex talionis,’ blood for blood, an eye for an eye, a life for a life.”

Burnett’s measure did not pass, though he remained a popular representative of Ontario County, holding his position until 1907 when he died of pneumonia – the same day his son Jean was born.

In 2004, NYS formally abolished the death penalty. Though host to two executions, a number dwarfed by neighboring and nearby counties such as Monroe and Cayuga, Ontario County and its residents were still deeply entwined with NYS capital punishment legacy.